Through Any Given Door – Part II

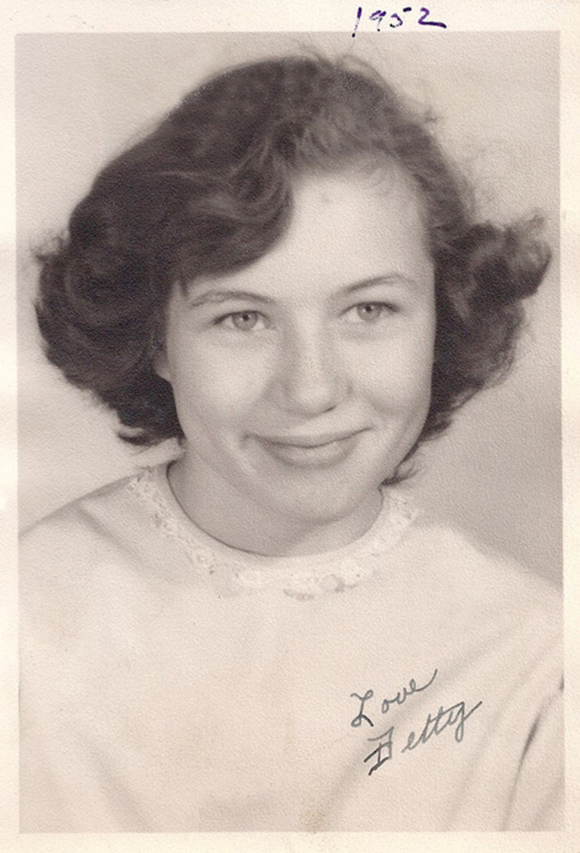

After finishing my family memoir some years back, including the account of my sister Betty’s rape, I connected with Betty’s childhood friend, Lorna Harrington, who read it and then wrote me about their friendship. I combined two of those letters here, as Lorna could tell their story better than I.

A recap of the family:

Carl Clemens (our father): born Sep 25, 1905, Minnesota.

Noreen (Chatfield) Clemens (our mother): born September 29, 1915, California, and married February 4, 1933, Colusa, California.

Their five children:

Larry Clemens: born Jan 14, 1934, Chico, California.

Carleen Clemens: born Mar 13, 1935, Watsonville, California.

Betty Clemens: born Dec 3, 1939, Watsonville, California.

Claudia Clemens: born Mar 28, 1942, Vallejo, California.

Cathy Clemens (me): born Aug 16, 1948, Sonora, California.

This is the letter to me from Lorna Harrington:

Dear Catherine, while trying to give you an idea of what our (Betty’s and mine) lives were like during our Sonora grammar school days, I didn’t think to explain that we weren’t the cheery, popular girls. Children who can’t invite friends to their home, or have birthday parties, remain apart from the cliques that school girls form. My mother didn’t like living in Sonora, or like 90 percent of its inhabitants, and was very vocal about it. She grew up in San Francisco and loved art, music, and lots of city variety, like your mother.

My mom explained to me when I was a teen that your mom found herself in a trap of having too many babies with a Catholic husband, with no personal outlets for fun or self-expression. I see from your mom’s letter to her sister that there was no family safety net for your mom, or for you, Claudia and Betty.

My two sisters and I were staying at our cousin’s home in Los Angeles during the summer after seventh grade when we were told we weren’t going home to Sonora. The following year, my father wrote, sending me a newspaper clipping about the savage attack on Betty. My world changed, and I knew Betty would never be the same. And she wasn’t. In 1953, Sonora was a small town, off the beaten track with no crime that we had ever heard of. Our schools had such good discipline and our streets were so safe that, as students, we were not aware of the possibility of being attacked. Yet Betty was grabbed off the main street while walking home, savagely beaten and raped while they talked of killing her. Hours later they threw her out of the car on a dark back road. She said she found a deserted building where she could break a window to get in and phone for help. But she told me that the nightmare continued with the sheriff’s men questioning her, the doctor’s exam, and then the trial when they caught the thugs. And she said people treated her strangely afterwards.

Later that summer, while visiting my father in Sonora, Betty and I spent what turned out to be our last few days together. We walked out of town and talked. She was still seeing a chiropractor because of the injuries to muscle and bone structure that came with the rape and beatings. We were thirteen and she always had been well built with great health, and from the outside she looked like the same old Betty. But she hurt, and she was troubled with questions, when before she had always been so sure of everything.

Betty loved her father, and I didn’t know what to say when she told me he had denied to a relative that she’d been raped. We talked it over and over and over, and the best I could figure was that our fathers were really old-fashioned and strict over anything to do with sex. Not allowing us makeup or formfitting sweaters, etc., and that they expected us to grow up, get married in white dresses as virgins, and the rape bothered Betty’s father so much that maybe he decided it would be best to deny it happened.

I am so sorry for the hard times and trauma you all went through growing up.

Love, Lorna.

Be First to Comment