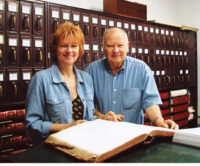

For three years, my Sonoma Sun column consisted of chapters of my family memoir. I took a break from it a year ago as grim events were coming up: The deterioration of my mother; the kidnapping and rape of my 13-year-old sister; my oldest sister’s high school pregnancy and marriage. It wasn’t going to work to have these stories in the paper. So, we’ll skip the details and jump back in here:

August 1953 • California to Minnesota and back

Wanting to get away from it all, Dad packed Betty (age 13), Claudia (age 11), and me (nearly 5) in the back seat of a new four-door 1953 Chevy Bel Air, and took us on a month-long trip to the Midwest to visit his family. My brother Larry (age 19) came home from college to help drive. We were in the car for so long that Claudia developed a jerky leg, bad enough that Dad considered taking her to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, where they had a whole building for patients with “restless-leg syndrome.”

After a week, we arrived at the Hausers. Aunt Agnes and her family lived on an acre of the old Clemens farm just outside Rochester. During our stay, Betty confided in our cousin Barbara, who was the same age, about what happened in Sonora. My sister, who hadn’t had a period for a couple of months, was worried she was pregnant. Out of concern for Betty, Barbara went to her mom with the story, and of course, Aunt Agnes went to Dad. When she finished, Dad looked away and said flatly, “It never happened. Betty made it up.” Aunt Agnes believed him. What was even worse, what wounded Betty more deeply than what those boys had done to her, was that Dad said she was lying.

Aunt Elizabeth took us to the Iowa State Fair where we won a baby duck. Betty’s only fond memory of the trip was eating molasses cookies just out of the oven, a specialty of Dad’s two spinster Nigon aunts.

Driving home straight through, we only stopped for gas, meals, and to bury the baby duck. Betty refused to get out of the car; she was busy reading her comic book. She read during most of the trip, slouched below the window beneath the passing landscape, her book held at eye-level. Claudia and I couldn’t even look at a book; we were carsick the whole trip, rising from the wells of the back seat just long enough to heave and read the Burma Shave signs dotting the eternal stretches of highway:

“This old world…

Wouldn’t be uptight…

If people simply…

Did what’s right…”

Burma Shave

After dropping off Larry in San Jose, the four of us drove home to Sonora.

Lorna Harrington, who was staying with her father in Sonora in late August and hadn’t seen her best friend in more than a year, held Betty’s hands when Betty told her what happened, told her how scared she was, and then told her what Dad had said about it afterwards. Lorna was furious; she told Betty that both their fathers were old, that they weren’t good with girls, that they said stupid things like “girls were women’s work” and that men didn’t get involved with women’s work. They didn’t know it, but it would be the last time the two friends would ever see one another.

Be First to Comment